I shot film for a long time before digital photography came along. The transition was difficult for many photographers, but I had it a little easier because I had already been working as a graphic designer, sending transparencies out for scans and working with the resulting digital files in layout.

I was still cautious in the early days of digital, however. I first bought an Apple Quicktake, then (I think) a Nikon 950, followed by a 990. My first DSLR was a Nikon D100 and, with that purchase, I began to seriously shoot digitally. I still shot film alongside digital, using my Nikon F100 film body, because some clients and publications were still uneasy about getting digital files from an assignment.

My last international trip with film was to Ireland in October of 2002. Heightened security at the airports was making it more and more difficult to travel with film and avoid x-rays. Honestly, it was also nice to no longer have to worry about how much film to take, what ISOs to choose, the expense of processing it all afterward, etc., etc.

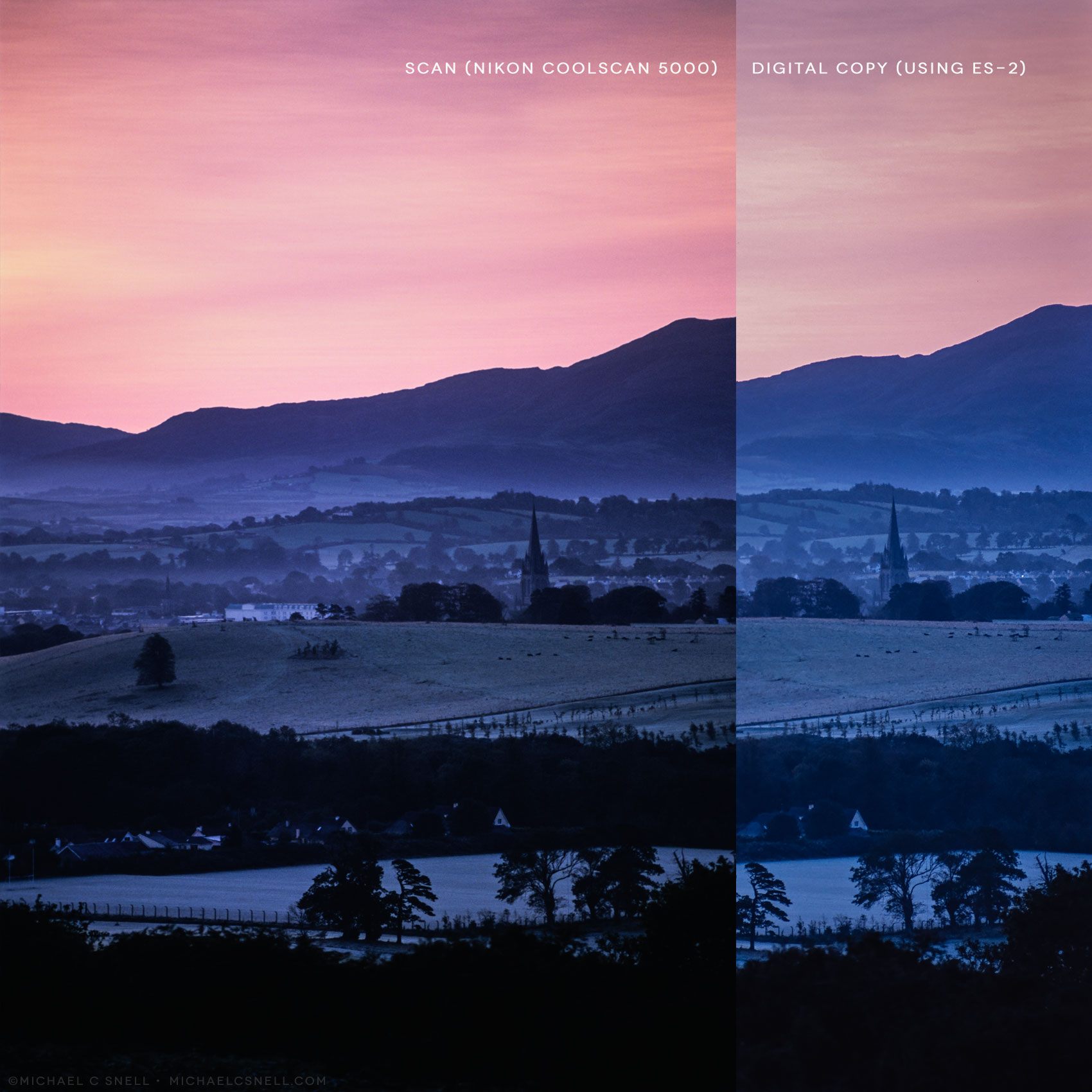

This is a long way of saying that, until around 2003, I was shooting a lot of film. And I accumulated a great number of transparencies. I would occasionally get drum scans of key images, but it was too costly to go back and digitize everything. I had a Nikon Coolscan (I forget the model number — 4000?), followed by a Coolscan 5000 which I still own. These dedicated slide scanners worked well enough, but they were slow if you went to the effort of multi-pass scanning — a sort of HDR for scanners where it made several scans to improve shadow detail, etc. Then, there was the dust-spotting of the scans. If you think getting rid of a few spots created by dust on your sensor is bad, try scanning a piece of film with two surfaces that are sure to attract some dust, regardless of how much you use a blower on it.

Scanning was never fun, but it was a necessity if you wanted to make use of your old archives. As scanners became hard to come by, I kept the old Coolscan 5000 along with the old tower Mac that it was connected to — via some cable or port that has long since disappeared from modern machines. Occasionally, when needed, I could fire the ancient Mac up and make a few scans. Less often had that been necessary as time marched on, but I still had some concerns about what to do when the old Mac or scanner finally gave up the ghost.

Enter the Film Digitizing Adapter

Recently, I spotted the Nikon Film Digitizing Adapter ES-2 and thought I’d give it a try. It’s basically a tube that connects onto the front of a macro lens, with some frosted plastic on the front and a rack that lets you insert 35mm slides into the tube. You point it into a lightsource (which the frosted plastic softens and evens out) and take a photo of the slide. Brilliant. So simple.

I had played with a similar DIY idea previously, shooting transparencies on a lightbox through a tunnel of black foamcore, and it was problematic — mostly with getting an even light source on my table. Would the ES-2 be any better?

I have to say, the results are pretty darned good — and it’s so much faster than sitting there listening to the scanner chug along. Your results will be somewhat reliant on the camera and lens you use, of course — afterall, you’re basically taking a new photo — but what I’m getting from a Nikon D810 and a 60mm macro lens is pretty equal to that of my scanner. Perhaps better, because I’m actually ending up with a larger file, thanks to the 36 megapixel sensor, and there might be a bit more shadow detail as well. I’ll have to test some more, but I think there might be a little less texture being picked up from the emulsion itself. That’s something I always felt was a part of the Coolscan 5000 output that I didn’t see so much of in drum scans (probably because the film was suspended in oil for a drum scan, eliminating any texture issues from the film’s surface).

Anyway… I’ll continue playing with the ES-2 and I’ll post a few more results in the future. For now, I’m pretty happy with it and my biggest disappointments are coming from the slides themselves. I have gotten used to the level of detail we have in digital files now, the silky-clean skies, the amazing shadow detail, and the sharpness! When I revisit some old slides that I was very happy with at the time, they now just look dark and soft to me. I have to admit, camera and lens technology has a come a long way and my work — and life — is the better for it.

Above — A photo of Killarney on a frosty morning 0n that 2002 trip to Ireland. Below is a version I scanned on the Coolscan 5000 a few years ago, compared to the new digital copy on the right. I have made no intention to match color, etc. at this point, I’m just sharing the difference/similarity in the detail and overall rendering.

Below — One more from 2002 Ireland, this time a morning stroll through Adare. The image at the top of this post is a slide I shot in San Francisco in September of that same year.